A couple months ago, my talented friend Mengyu texted me to ask if I’d write the text for a photo series she worked on, which she later named ‘The Filial Daughter 孝女’. (We’d met in Berlin a few summers ago. She DM’ed me when I was in town, we grabbed coffee, and immediately got along.)

I said yes — I’d never written text for an artist before, and it seems like something cool writers do. Plus, an excuse to catch up with a friend.

We’ve chatted a few times since: Mengyu’s photos ended up showing as part of a group exhibition at Konnekt Berlin (you can still see them until the 23rd, go!), and I got to interview her for a feature in AnOther Magazine, a lovely full circle moment.

Over the course of our correspondence — for the text, for the feature — I thought of publishing more of our conversations here, along with the original text. I think what’s out there already does a good job of capturing the essence of the photos, but I wanted to give Mengyu more space to speak to her and her cousin Orange’s experiences. A 700 word article can only include so much!

So, below is my original text for the project, along with a transcript from a Zoom call we did two weeks ago. It’s a somber read but I think you’ll understand why I wanted to give it more room.

There is no concise English translation for the Chinese character, 孝 (xiao). The closest analogue is "filial piety" which still fails to evoke the ubiquity of the Confucian-rooted virtue, and how the expectations around respecting one's parents and elders have shaped China as a whole.

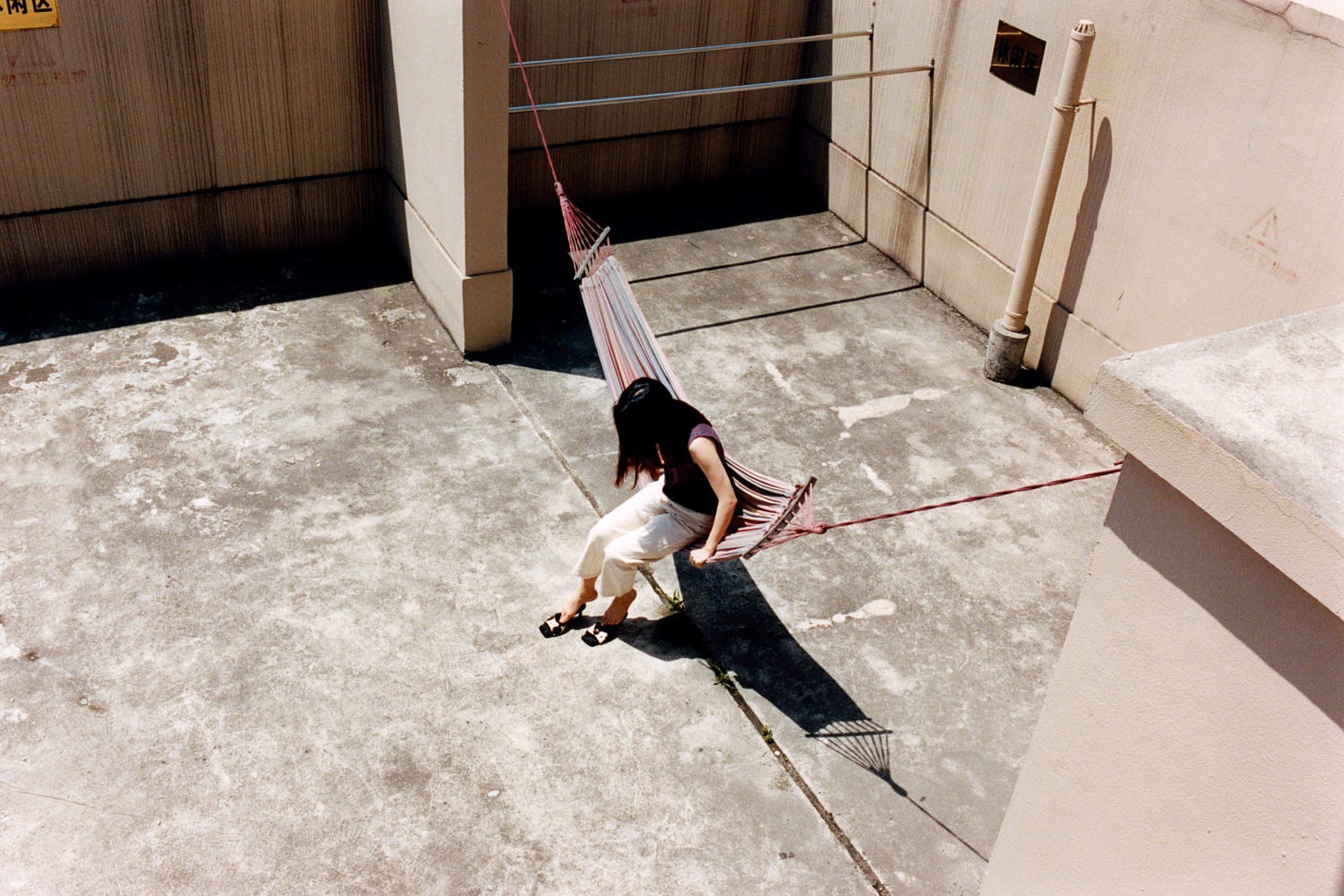

In Mengyu Zhou's photo project The filial daughter 孝女 — the second character (nü) meaning daughter — she offers an atmospheric depiction of young womanhood confined by familial and societal norms. Between shots of dusk-lit cityscapes and old family albums, its protagonist and Zhou's cousin, Orange, goes about her day in a languid but pensive state. But studies of the seemingly mundane are far from it, deftly illustrating the monotony of a life lived for collective, as opposed to individual, gratification.

Born in 1994, Orange grew up with Zhou in Wenzhou, a port and industrial city in China's Zhejiang province. After Zhou moved to Germany, where other family members already resided, Orange, who had always dreamed of living abroad, decided to drop out of high school and apply to programs in the country, only to have her parents secretly cancel her application.

Without a high school diploma, Orange filled her days by doing odd jobs and was labelled a poor marriage prospect, with youth being her only redeeming quality. Having met a boy in her early 20s, she was told to marry or be set up with someone else; the two wedded but their union ended within a year.

Only just relieved of the pressures around marriageability, Orange was faced with the stigma and shame dealt to a female divorcée. Nonetheless, the end goal remains unchanged: she is still being pressured to remarry.

Despite meeting obstacles at every turn, Orange hasn't lost her desire to live her own life abroad, unencumbered by the objectifying and oppressive dogmas older generations maintain. But like many Chinese women of her generation, she’s been delegated a role she can't quite escape. The values and virtues around being a good daughter — of sacrifice, of selflessness, of devotion — require her to accommodate everyone else's emotions and expectations but her own. These anachronisms are so deeply ingrained in her self-worth, that the cultural and personal bleed into one familiar yet isolating mass.

In spite of her troubles, Orange — as she gets dressed, as she kills time in a car, as she listlessly sits on a hammock baking in the sun — is pictured with the intimate gaze only sisters and best friends share. In some ways, hers is a life Zhou would be living if she didn't have the opportunity to leave. This emotional proximity, in spite of the different trajectories their lives have taken, is palpable and layers the images with bittersweet understanding.

Just as apparent is a feeling of airlessness, of ennui, of waiting for a life to begin as it passes. The sepia-hued family portraits and shots of the city — a patchwork of promising concrete newness against ancestral history, religion, and natural scenery mirroring old landscape paintings — depict the frictions at play. Yes, skyscrapers may now tower over Wenzhou's muddy riverbanks and verdant grassy fields, but this so-called progress is still far removed from the fabric of everyday life and the younger generations growing up in a "new" China.

While Orange's story is unflinchingly personal for both her and Zhou, a sense of disenchantment, of being left behind by growth, is common: just look up headlines around gruelling '996' work culture, 躺平 (tang ping) a.k.a lying flat, or 擺爛 (bai lan), letting it rot. But the photographs are all the more poignant for the subtle way they zoom in and capture what this means for women — specifically those trying to find meaning in a culture that, for all its strides forward, continues to be tethered to stifling patriarchal traditions at the cost of female selfhood.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Floss to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.